I have, once more, neglected to write anything for quite some time. I even found a paper from at least a week ago with various comments I gathered from my reading of the texts. At this point I doubt I'll understand them much but I want to take care of them as best as I can so as to be capable of moving on.

Yates

-Camillo's memory theatre drew from many ideologies as he attempted to contain the entire universe in his memory. He illustrated this goal with imagery of finding oneself within a forest and being unable to form a clear picture of the forest or one's place in it without climbing to the top of a high hill that overlooks it all. Yates quotes Camillo as saying, "in order to understand the things of the lower world it is necessary to ascend to superior things, from whence, looking down from on high, we may have a more certain knowledge of the inferior things."

-A memory system of this scale, particularly the seven parallel gates, is a systematized version of the traditional memory theatre we've seen before. Although Camillo deals with symbols and concepts I do not easily relate to, I would consider creating something like this for myelf for the purpose of exponentially expanding my capacity to remember. My current theatre works very linearly and simply. This is good for contained stories and lists. I would like to accomplish a more wikipedia-like memory system without simply complexifying each locus. How, precisely, i don't know yet.

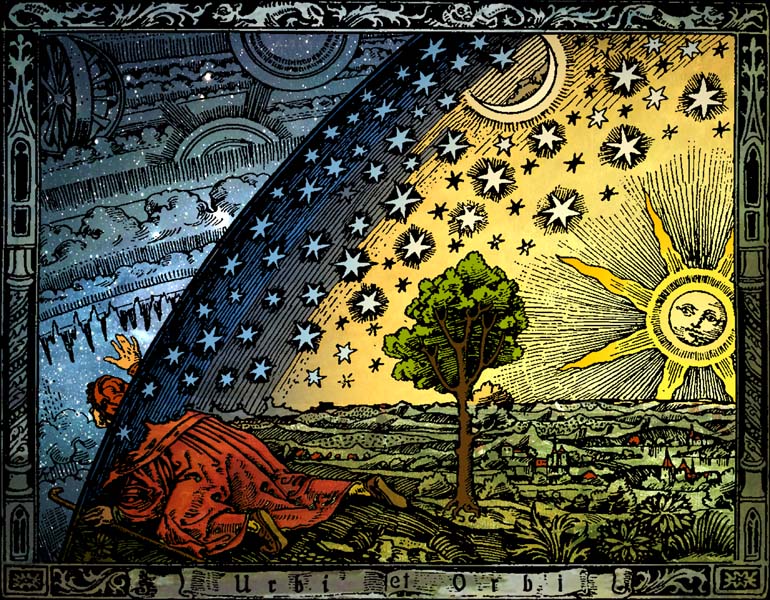

-One last thought with this. Yates sums up Camillo's feat not simply as "a highly ornamental filing cabinet" but as an idea "the Idea of a memory organically geared to the universe." This brought to mind an image that has always fascinated me known as the "Flammarion woodcut" which I will not explain but have posted above.

Ong

-Print is imbued with a sense of closure, which is part of the reason I have trouble getting myself to write things down, yet can talk forever. I have "communication commitment issues" in that respect.

-The relationship of sounds and words and letters brings to mind waveform. Waveform is the most literal visual interpretation of sound (though it would be next to impossible to read and write with it). Most people are familiar with how it looks, the squiggly lines you see on music visualizers, and in some of our classes for film we had to edit these patterns. You have a general pattern (flat means silence, spike means a loud noise) but the more you zoom into it the more detailed it becomes. Words are rarely tidy little pieces like they are when printed, everything mushes and slurs together in waveform and reminds me of the early texts where the idea of spacing hadn't come up yet.

"My Book and Heart Shall Never Part"

"My Book and Heart Shall Never Part"-I borrowed this short film from Professor Sexson (which he and his wife, Lynda, created). Using fictional and nonfictional elements the film examines 18th-19th century children's books, their origins, and how they shaped our culture. I found the subject very intriguing, but what best pertains to our class at the moment is the educational nature of most of these books. Of particular note are the books that teach the alphabet through simple images and sayings "The Eagle's flight is out of sight" for the letter E, for example. Books like these were a natural transition between the letter and image memorization aids we see in Yates chapter five and our often less compelling modern works "A is for Apple, B is for Ball." Going along these lines and the common class theme of using grotesque imagery I invite you to read through Edward Gorey's "The Gashlycrumb Tinies" found here.